Key Insights:

- FATF plays a critical role in setting global standards for combating financial crime, particularly money laundering and terrorism financing. Its recommendations influence the operations of over 200 countries and jurisdictions and shape the compliance strategies of financial institutions worldwide.

- Defining virtual assets and virtual asset service providers under FATF guidelines might be hard. In this article, we will try to overcome those challenges and break everything down.

- Following the FATF document, we will also address the difficulties in applying FATF guidelines to the P2P platforms and DeFi sector.

When 35-year-old Josh Martin* got a task to ensure his bank followed international crypto regulations, including FATF, he felt confused. He has been a compliance officer for a mid-sized bank for the past ten years and knows the ropes. Now, he feels like he is being put to the test.

Always double-checking work to make sure he doesn’t miss any detail, Josh decides to get to the bottom of it. To develop a new compliance framework for the bank’s crypto services, he must first understand the FATF’s recommendations on virtual assets and service providers.

*Josh Martin is a fictional character designed to illustrate the complexities faced by compliance officers in navigating the landscape of the FATF recommendations. His experiences mirror real-world challenges in the financial sector, showing a relatable and practical perspective on how professionals adapt and respond to regulatory changes. We hope his story will help you understand the intricate processes of compliance and regulatory adherence better.

FATF sets standards for combating financial crime

Founded in 1989, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an international policymaking group created to fight money laundering and terrorism financing. Its recommendations are recognized as the global anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) standard. Over 200 countries and jurisdictions have committed to implementing them.

FATF and FATF-style regional bodies

FATF also keeps track of how countries adopt anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing measures, promoting these practices worldwide.

In 2014, the organization released Virtual Currencies: Key Definitions and Potential AML/CFT Risks to address new value transfer types and potential risks.

“As a bank compliance officer, I balance new technology and the rules we need to follow daily. Cryptocurrencies offer great opportunities, but they also come with big risks. FATF highlights that virtual assets can be used anonymously and operate across borders, making them hard to track.”

Josh Martin

FATF updated its guidance four years later to add definitions for virtual assets (VAs) and virtual asset service providers (VASPs). And in 2019, its first version of a risk-based approach was released. Later, it was updated to meet the industry changes.

Note: These FATF regulations are applicable when virtual assets are converted into fiat currency and when there is a transfer or exchange between different types of virtual assets.

In FATF’s terms, a virtual asset is a value-bearing digital entity

FATF defines a virtual asset as a type of digital entity representing value. It includes any form that can be traded, transferred, or used for payment purposes in the digital space—stablecoins as well.

! However, this definition excludes securities and digital versions of traditional fiat currencies, i.e., CBDC—central bank digital currency.

Here is how Josh analyzes whether two currencies can be considered VAs.

- Currency A: Bitcoin (BTC)

- Nature: Bitcoin is one of the first and most well-known cryptocurrencies operating on blockchain technology.

- Usage: It is used for various online transactions, such as investments, trading on cryptocurrency exchanges, purchases, and peer-to-peer transfers.

- Characteristics: Bitcoin can be traded on numerous cryptocurrency exchanges globally for other digital assets and fiat currencies. Users can send BTC to anyone worldwide without the need for traditional financial institutions. It is accepted as a form of payment by some merchants.

→ Bitcoin perfectly fits the FATF’s definition of a virtual asset. It’s a digital entity of value that can be traded, transferred, and used for payments.

- Currency B: Digital Yuan (e-CNY)

- Nature: The Digital Yuan is a digital currency issued by the People’s Bank of China, serving as a digital counterpart to the traditional Chinese Yuan.

- Usage: Intended for everyday transactions and digital payments within China, mirroring the functions of physical currency.

- E-CNY is issued and regulated by China’s central bank. It’s a direct digital equivalent of the Chinese Yuan, a fiat currency. The Digital Yuan is designed for regular transactions and is not traded on cryptocurrency exchanges like decentralized virtual assets.

→ The Digital Yuan does not align with the FATF’s definition of a virtual asset. It is a central bank digital currency (CBDC), representing a digital form of China’s fiat currency. It is centrally controlled, thus falling outside the scope of what FATF categorizes as a virtual asset.

“In summary,BTC is an example of a virtual asset because of its decentralized nature and versatility in digital transactions. E-CNY is considered a digital form of a fiat currency and is not a virtual asset by FATF standards.”

Josh Martin

FATF defines VASPs through their core services

To be considered a virtual asset service provider, an individual or business entity not already covered by existing recommendations should be:

- Exchanging VAs for traditional currencies

- Trading different types of VAs with each other

- Transferring VAs

- Managing or safeguarding VAs, including services that allow control over these assets

- Involved in and offering financial services linked to an issuer’s sale or promotion of VAs.

It includes:

- Exchanges

- Crypto ATMs

- Crypto payment service providers

- Custodian wallet providers.

“Let’s imagine two examples. Service A allows users to convert crypto like Bitcoin and Ethereum into fiat currencies such as USD or EUR and provides wallets to store assets securely on the platform. It meets two criteria and can be considered a VASP.

Josh Martin

Service B runs an online gaming platform where players can earn and spend virtual currency just in that game. This currency can’t be turned into real money or traded for other digital assets outside the game but can be sent to another gamer within the game. Service B does not meet the criteria for being a VASP. Although it involves the transfer of in-game currency, these assets can’t be exchanged for fiat currency or other digital assets.”

VASPs not only offer a range of services but also operate on a global scale, serving clients across international markets. Given their international presence, is it essential for VASPs to acquire multiple licenses to adhere to the distinct requirements of the various countries in which they operate? The short answer is yes. Let’s break it down.

Does a VASP need a few licenses if operating in multiple countries?

It depends on these criteria defined by FATF:

| Criterion | Need for registration/license |

| The country where the company is incorporated | Always required |

| Location of management | Sometimes |

| Location of servers/back-office functions | Sometimes |

| Countries with significant numbers of customers | Sometimes |

Let’s explore how Josh evaluates the two following scenarios:

- Service A: Coinbase

- Country of incorporation: United States

- Location of management: Primarily in the United States, with regional teams and offices in various countries, including the UK and Japan

- Countries with the most customers: United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and several European countries.

→ Coinbase, set up in the US, is regulated under US financial laws, including compliance with SEC regulations and the Bank Secrecy Act. The global reach of its management and operations necessitates adherence to local laws in each country where it has a presence, especially concerning data protection, financial transactions, and anti-money laundering measures. Coinbase must also consider the legal frameworks of countries where it has a significant customer base.

- Service B: Bitbuy

- Country of incorporation: Canada

- Location of management: Entirely within Canada

- Countries with a significant number of customers: Largely Canadian customer base, with some users in the United States.

→ Bitbuy, a Canadian-based platform, primarily operates under Canadian financial regulations and securities laws. Its entire management is located in Canada, which simplifies compliance, focusing mainly on Canadian data protection and financial constraints. However, serving US customers, even if only a minor portion, requires Bitbuy to comply with specific US regulations related to crypto transactions, especially for cross-border activities and data protection.

“So, Coinbase, with customers and operations worldwide, faces a complicated mix of laws in different countries, especially in the US and Europe. On the other hand, Bitbuy mainly follows Canadian rules but also keeps an eye on US laws because it has some customers there.”

Josh Martin

P2P platforms can be classified as VASPs depending on how they operate

FATF views ‘peer-to-peer’ (P2P) transactions as exchanges of VAs that happen directly between two people without involving a regulated financial service. These are often transfers between personal crypto wallets.

These transactions aren’t directly controlled by AML/CFT rules, but FATF suggests that countries should keep a close eye on P2P transactions.

For platforms offering these services, it matters if they help with the transactions:

- If a P2P platform just lets users trade directly without getting involved (e.g., providing custody services), it might not count as a VASP.

- But if the P2P platform actively helps with trades, offers escrow services, or controls the transactions in any way, it’s likely seen as a VASP. This classification would subject it to FATF’s AML/CFT regulations.

“Thus, whether a P2P platform is a VASP under FATF standards hinges on its level of involvement in the transactions. The more it acts as an intermediary or facilitator, the more likely it is to be seen as a VASP”

Josh Martin

The FATF rules are for both countries, VASPs, and other businesses that work with virtual assets. This includes banks, those who deal in securities, and other financial institutions.

Qualifying DeFi as VASP/non-VASP is hard

The FATF guidelines instruct countries to evaluate each DeFi (decentralized finance) entity individually to decide if it qualifies as a VASP. The key point is that entities controlling or influencing DeFi protocols and those involved in offering or assisting VASP services must adhere to AML and CFT regulations. This includes entities that:

- Regularly interact with users of DeFi protocols, for example, Uniswap, a popular protocol for exchanging crypto.

- Make profits from these services like Aave, a DeFi lending platform.

- Or have the power to modify the protocols’ settings (this aspect is challenging to assess because, in many DeFi services, token holders play a crucial role in the protocol’s development).

It’s quite challenging to determine if a particular DeFi service counts as a VASP. Decentralized apps (dApps) themselves aren’t virtual asset service providers. But in many dApps, there is usually a main entity responsible for running the platform, like establishing its rules, managing access, or earning fees. These entities could be considered VASPs. Moreover, owners and operators are likely to be qualified as VASPs.

Let’s check an example.

MakerDAO—decentralized lending platform

- MakerDAO uses a decentralized governance model where decisions are made through community voting by token holders. This structure complicates the application of traditional regulatory frameworks like those for VASPs.

- MakerDAO facilitates the creation of DAI and the management of collateralized debt positions. It could influence its classification as a VASP.

- Different countries might apply FATF guidelines differently, so MakerDAO could be seen as a VASP in some jurisdictions but not in others, based on local laws.

“In conclusion, MakerDAO’s decentralized approach and its involvement in digital currency and lending activities place it in a complex regulatory position. Whether it’s classified as a VASP depends on specific local laws and how these interpret international guidelines”

Josh Martin

Now, when the key definitions are established, how can VASPs implement them? This is exactly the subject of the Updated Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach for VAs and VASPs.

FATF’s guidelines don’t automatically label any industry as a higher risk. However, a risk-based approach is needed for a more flexible and effective response to the challenges posed by the virtual asset industry.

Each year, $2 trillion is laundered, according to the FATF estimates. Less than 1% of illicit financial transactions are recovered. Moreover, illicit activities in the crypto sector are on the rise. In November 2023, the industry experienced its most significant losses due to theft, fraud, and various exploits. Cybercriminals illicitly acquired an unprecedented total of $363 million.

So, it’s better to evaluate the risks in advance. That’s why crypto companies and financial organizations use this method for comprehensive assessment. Advanced blockchain tools make it easy for compliance teams to assess risks and monitor transactions daily, in line with FATF guidelines.

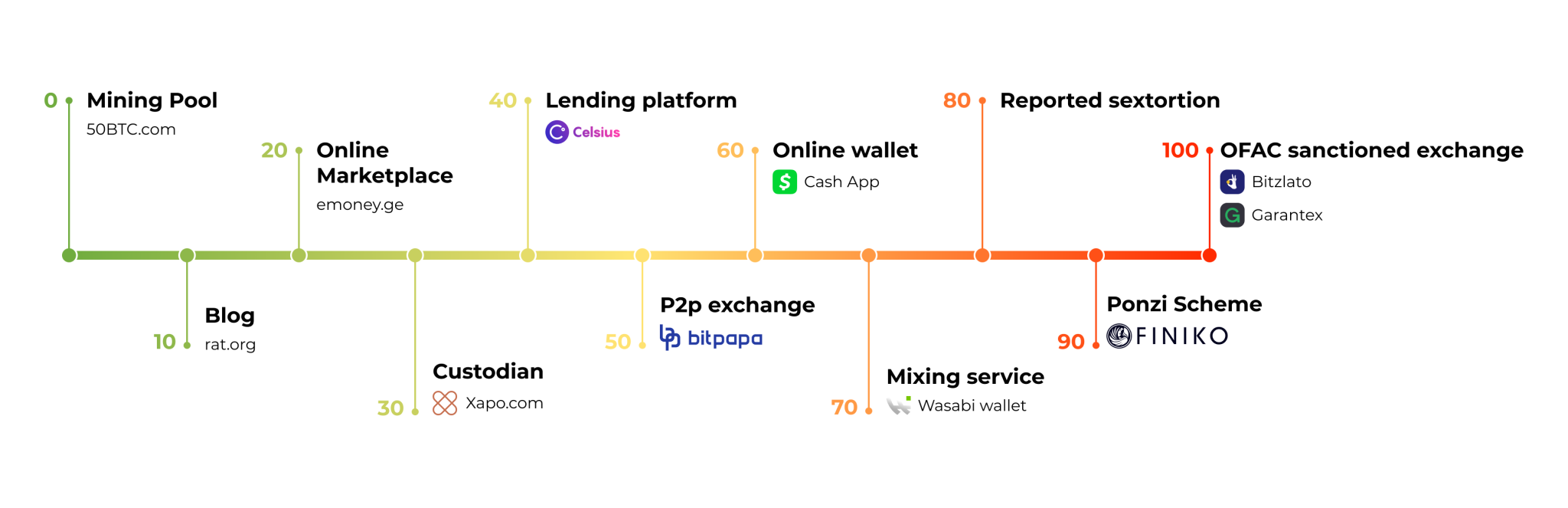

Scheme showing how GL assigns risk scores to different entities, with 0 being the lowest risk score and 100 the highest

In Part 2, we will delve into effective strategies for crypto businesses to align with FATF standards, exploring practical approaches for implementing these regulations and understanding the nuances of compliance in a digital currency context.